1. Perspective

Stanford scored an offensive touchdown on its first possession. It failed to score another offensive touchdown. It is almost impossible to beat a good football team when your offense goes 56 minutes without scoring a touchdown.

2. The Players

It was an evenly played game. Both defensive lines dominated, and both quarterbacks threw the ball fairly well downfield. (Cook had many more yards but threw twice as many passes as Hogan.) The main difference that stood out to me was a few key plays by defensive backs. Michigan State defender Trae Waynes made a great interception on a pass that was almost caught by Michael Rector. Stanford defensive backs did not make big plays at big times. Stanford defender Wayne Lyons dropped an easy interception and Stanford cornerbacks had two crucial holding penalties. Those were huge plays in this game. (Another turning point was the missed interception by Kevin Anderson. Instead of Stanford having a chance to go up 17-0, Michigan State continued the drive and narrowed the game to 10-7.)

3. The Coaches

MSU coach Mark Dantonio called a good game. After it became clear Stanford was going to shut down the Spartan running game, Michigan State shifted seamlessly into an air attack. During one drive in the middle of the first half, Connor Cook dropped back to pass on seven consecutive plays. In the 3rd quarter, when Stanford had later shifted its personnel to defend the pass, Langford picked up 34 yards on four consecutive carries.

The Stanford coaching staff failed miserably.

(Note: Because I don’t know exactly who called which play, I’m going to just refer to David Shaw when discussing game management and play-calling. Stanford has gone back and forth in stating who actually calls the plays. At one point in the season, it was reported that Mike Bloomgren calls the plays except when Shaw takes over in the Red Zone. But Shaw has also said that set nothing is set in stone and that he regularly takes over all play-calls at any point in the game. And when ESPN showed the Stanford sideline, it always looked like he was making the call.)

4th and 1 with the Rose Bowl on the line, and out comes the elephant package. My heart sank. Unless a trick play was about to happen, the game was over once that play was called. After the game, Tyler Gaffney said, “You have to give it to Michigan State for stuffing that because everybody in the building knew exactly what was coming—a run was coming up the middle—and it was a test of wills, and they got the better of us.” That is one perspective, and it is the mature and noble thing to do to give credit to Michigan State. Their defensive line was awesome. But reading between the lines reveals a sad truth—Michigan State knew what play Stanford was going to run. In most Stanford games, there isn’t a need for deception or timely coaching. Stanford can often completely stop thinking and just win the battle at the line of scrimmage. But the offensive line was not going to win this battle. In my opinion, the Michigan State defensive line had already won the battle by the end of the 2nd quarter. It is objective fact—as I’ll explain below—that the Spartans had won it decisively by the end of the 3rd quarter. Everyone in that stadium knew it. Everyone watching at home knew it. My girlfriend, Vicki, who is not a football fan, knew it—“It’s like they’re just wasting downs,” she said. David Shaw didn’t know it. Or he refused to believe it. The play-calling in the 2nd half reminded me of a stubborn father forcing a son to do something again and again, even though the child is obviously struggling. It reminded me of the kind of drills a team might do in practice, when the offensive line isn’t meeting an expectation. Repeat. Repeat. Let’s get it right. Try it again. Repeat… But this wasn’t practice. It was the Rose Bowl, and Shaw isn’t getting paid millions to act this way in the Rose Bowl. The goal is to win the game. And Shaw utterly failed at managing the game.

Let’s explore the facts that show why Stanford should have abandoned the running game in the 2nd half. Gaffney had a couple nice runs on the opening drive. After the first drive, there were only two successful Gaffney running plays: 47-yard gain and a surprise run up the middle on 3rd and 12 that went for 9 yards. (I actually don’t mind the call to run on 3rd and 12, since it is one of the few times that Shaw was unpredictable.) Ignoring the first drive of the game, and the 47-yard gain also in the 1st quarter, Gaffney gained 22 yards on 22 carries. Get out those calculators, this one comes out to: 1 yard/carry.

The low point came in a third quarter drive when the futility of running the ball was starting to be very apparent. During one stretch from the 1st to 3rd quarters, excluding the surprise 3rd down run for 9 yards, Gaffney gained minus 2 yards on 10 carries. The last of these 10 carries came on a crucial 4th and 3 play in Michigan State territory. At that point, it was objectively clear—minus two yards on the last ten carries—that predictable runs up the middle were not working. Here is some more perspective for just how dramatically unsuccessful the running game was at that point: coming into the Rose Bowl, Tyler Gaffney had been tackled behind the line of scrimmage 16 times in 13 games. That is an average of 1.23 times per game. With 4:10 remaining in the 3rd quarter, Gaffney had already been tackled for a loss six times.

At that point, with 19 minutes remaining in the game, Stanford’s primary identity was obliterated. Adapt, or die. Stanford would have to ride Hogan’s arm to victory.

Instead, on its next possession, Stanford handed the ball off to Gaffney on three consecutive plays, and promptly punted. Still in the 3rd quarter, Gaffney had now been tackled for a loss seven times. OK, so now we’re getting the idea. Let’s get Cajuste on the loose again. Inconceivably, on the following possession, Gaffney ran up the middle on 1st and 2nd down, bookending a streak of six consecutive (unsuccessful) Gaffney runs up the middle.

In the fourth quarter, Hogan only threw three passes, and Gaffney received six carries. Just unfathomable stuff. Stanford would have had a better chance to win if the Stanford coaches would have been removed from the sideline and replaced by a random fan who simply told Hogan, “You got this… just call whatever passing play feels right. If they ever drop into deep zone coverage, use your legs.”

Let’s look at three other coaching errors, two of them critical.

Timeouts. Shaw needs to be able to make a call on fourth down without taking a timeout. Stanford burned timeouts it could have used at the end of the game to get one last possession, even after the failure on 4th and 1. (I’d cut Shaw some slack if Stanford emerged from those timeouts in a creative formation for a novel play.) Those wasted timeouts really hurt Stanford, since its defense had the momentum to make another stop.

Deep in Your Own Territory. At some point coaches like Shaw should learn that being stuck inside your own ten yard line is a great opportunity to take a shot downfield. The one time Stanford did throw deep from inside its own ten, Hogan completed a 51-yard pass to Cajuste. Defensive coaches like to load the box, both expecting a run and trying for a safety. Receivers have a great chance to beat single coverage for a big gain. But offenses seem to worry too much about taking safeties and getting room for their punters. Stanford was excessively conservative in these situations.

Field Goals Instead of Touchdowns. Shaw, like most coaches, attempts too many field goals. But because Stanford has a good kicker and a great defense, Stanford should attempt more field goals than the average team. Still, there are certain situations when it kicking a field goal is undeniably the wrong decision. In the 4th quarter, down by 7 points, with only 4:15 remaining in the game, Stanford faced a 4th and 5 from the MSU 17 yard line. Let’s analyze some statistics related to the decision of kicking versus going for it. First of all, let’s completely ignore the game situation (down 7 points late) and just compare expected outcomes. Here’s the stats we’ll use:

- Stanford kicker Jordan Williamson is 22/27 (81%) on kicks of 30-39 yards for his career.

- In 2013, Stanford was 25/54 on third down conversions from 4-6 yards. That is 46% conversion rate. (There isn’t enough data for 4th down, and 3rd down situations translate well to 4th down.)

- In Stanford’s 51 trips (prior to the drive) into the red zone in 2013, Stanford has scored an average of 5.06 points per possession.

Let’s assume that if Stanford picks up the first down, then it translates into an average red zone scoring situation. (It might be slightly better than average because Stanford would have been inside the 12 yard-line, but slightly worse than average because of Michigan State’s defense—MSU’s defense allowed 4.27 points per red zone possession in 2013.) So, the expected points going for it = (chance of converting on 4th) * (points per red zone possession) = .46 * 5.06 = 2.33 points. The expected points from field goal attempt = (FG %) * 3 = .81 * 3 = 2.43 points.

The expected value from the field goal attempt is higher—primarily because Williamson is an above-average kicker—but it is only slightly higher. When you are losing by 7 points late in the fourth quarter, you need a touchdown! It is unquestionable that you increase your chances of winning by going for it. (I’m not going to do the math on this now.)

Shaw sent in the field goal team. But wait! It was a fake field goal! “Brilliant! Brilliant!” I yelled maniacally, as the holder rolled out and completed the pass. I haven’t seen us attempt a fake field goal in years! Oh, so brilliant! “Yes, Shaw! Yes, Shaw!” I screamed. Unfortunately, the play came back on a penalty. And then I saw the replay—it was a mishandled snap. Ahhh… of course.

Shaw is a brilliant coach and should prepare, nurture, and lead Stanford’s football team for many years. But in my mind, he needs to turn the over the in-game management duties to someone who is more capable.

4. The Pac-12 Bowl Season

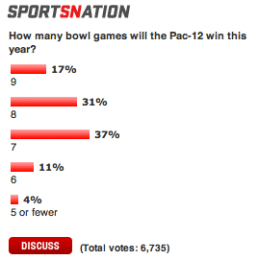

The Pac-12 went 6-3 in bowl games. Was it a successful bowl season? Expectations were high for the conference, as Pac-12 teams were favored in all nine games. But it seemed like expectations were a bit too high. On Dec 16th, the ESPN Pac-12 blog (above graphic) showed that of 6,735 voters, 85% of them expected the Pac-12 to win at least 7 games. These numbers are biased because readers of the Pac-12 blog are likely to be hopeful and loyal fans of the conference, but the survey results still showed a very inflated sense of confidence. In my previous blog post, I also let my bias skew my thinking and wrote that I expected the conference to win 7 or more games. However, Pac-12 blogger Ted Miller correctly predicted the tipping point for a successful bowl season at 6-3. We can back up his intuitive expectation using the mathematics of expected outcomes. To determine what the expected results were, we need to translate the spread (line) to a percent chance of winning. People use different data to determine this, and I estimated my numbers using a few different sites. Here’s one. My numbers are actually slightly on the high side of these estimates. In other words, while I estimated Oregon’s chance of beating Texas at .85, most estimates would probably fall in the .80-.85 range. So, if anything, my numbers are slightly inflated towards Pac-12 success. The results, however, show a tempered reality. Despite being favored in all 9 games, the Pac-12 was more likely to win six or fewer games.

The Pac-12 went 6-3 in bowl games. Was it a successful bowl season? Expectations were high for the conference, as Pac-12 teams were favored in all nine games. But it seemed like expectations were a bit too high. On Dec 16th, the ESPN Pac-12 blog (above graphic) showed that of 6,735 voters, 85% of them expected the Pac-12 to win at least 7 games. These numbers are biased because readers of the Pac-12 blog are likely to be hopeful and loyal fans of the conference, but the survey results still showed a very inflated sense of confidence. In my previous blog post, I also let my bias skew my thinking and wrote that I expected the conference to win 7 or more games. However, Pac-12 blogger Ted Miller correctly predicted the tipping point for a successful bowl season at 6-3. We can back up his intuitive expectation using the mathematics of expected outcomes. To determine what the expected results were, we need to translate the spread (line) to a percent chance of winning. People use different data to determine this, and I estimated my numbers using a few different sites. Here’s one. My numbers are actually slightly on the high side of these estimates. In other words, while I estimated Oregon’s chance of beating Texas at .85, most estimates would probably fall in the .80-.85 range. So, if anything, my numbers are slightly inflated towards Pac-12 success. The results, however, show a tempered reality. Despite being favored in all 9 games, the Pac-12 was more likely to win six or fewer games.

The first step towards determining the expected outcome involves getting an average winning percentage for the 9 games. Then, it is just a matter of calculating the various combinations. (The win percentages are in chronological order of the bowl games: WSU = .64 , etc…)

Chance of winning any one game = (.64 + .67 + .58 + .58 + .85 + .85 +.70 +.70 +.61) / 9 = .68666… or (103/150)

9 Wins: 9C9 • (103/150)9 = .0339

8 Wins: 9C8 • (103/150)8 • (47/150)1 = .1394

7 Wins: 9C7 • (103/150)7 • (47/150)2 = .2544

By adding up the chances for 7, 8, and 9 wins, we see that there is only a .4277, or 42.77%, chance that Pac-12 teams would win 7 or more bowl games. Clearly, my assertion that I would “take the over on 6.5 wins” was a bad bet. 6 wins turns out to be the most expected outcome, just slightly more likely than 7 wins. (The probabilities drop dramatically after 6 wins.)

6 Wins: 9C6 • (103/150)6 • (47/150)3 = .2709

So, it is fair to say that the Pac-12 met its expectations for the bowl season. In fact, one could still claim it exceeded them, considering that the margin of victory in all six wins was 15+ points. Plus, Washington State should have… I mean… well… it really punched itself in the groin. If Mike Leach could—or was willing—to do some simple math and have his team take a knee in the final two minutes, then the Pac-12 would have notched an impressive seven victories.

Thanks for another excellent analysis of a Stanford game. A tough loss in a game we should have won. Hopefully Shaw will adapt to this loss and be less obvious in his play calls. And I’m hoping the jumbo package goes away against all but the easiest opponents. I think we can run more effectively from a 2-3 receiver set where the gaps are spread and there is some uncertainly on the play calling.

Thanks for the thoughts. I agree. If we can win by using the jumbo, that’s great–it means there will be less plays on film for future opponents to watch. But the jumbo package should not be used in tight games.

A good read.

On the conference level, I’d give the conference a C at the most in post-season. The reason is that the marquee teams (both division champs) both lost, which makes the conference look lackluster and unimpressive. I think that the Pac-12 may be the deepest conference in the country, and strong in the middle, but the top teams are in no way as strong as the top teams from other conferences, including the B1G, which is not as deep but much better at the top, as we saw with MSU’s complete and utter domination of Stanford for three quarters.

Thanks for the comments. I think a C is a fair grade. As much as I hate to admit it, I think you are correct that the top of the Pac-12 is weaker than the top of some other conferences. Oregon has lost in the big games vs the SEC, and Stanford lost both its BCS games against top-5 teams. (Its two BCS victories were against over-rated Virginia Tech and a 5-loss Wisconsin.)

But with regards to Big10 vs Pac12, I would take Stanford and Oregon against Michigan State and Ohio State any day of the week. I would give MSU a very slight edge over Stanford if they were to play again, and I would give Oregon a fairly solid edge over Ohio State. Here’s one piece of data to back that up: Ohio State gave up 34 points and over 500 yards to Cal; Stanford and Oregon both absolutely crushed Cal.